The Geology of the Carolinas: Deep Time and the Formation of North and South Carolina

- Nov 1, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Feb 7

Introduction: Landscapes Built From Violence

The Carolinas are looking pretty chill today with their rolling Piedmont hills, blue-gray mountain ridges, and the wide, flat stretch of the Coastal Plain. But underneath this calm surface is a wild story of massive collisions that stuck continents together, volcanoes popping up like islands in the Pacific, oceans opening and closing, and mountains that once soared higher than the Himalayas.

To really get the geology of North and South Carolina, you need to imagine a time span of over a billion years. The land under places like Charlotte, Columbia, Greenville, Asheville, and Newberry was put together bit by bit through intense continental clashes, ages of erosion, and the slow movement of tectonic plates. The landscape we see now—peaceful, wooded, and familiar—is just the last few moments of a much longer story.

Long Before the Carolinas: The Ancient Core (~1.2 billion years ago)

The oldest rocks in the Carolinas are from the Grenville Orogeny, a massive collision that helped create the supercontinent Rodinia about 1.2–1.0 billion years ago (Tollo et al., 2010). These rocks are now buried deep under the Blue Ridge and parts of the Piedmont.

Back then, what we now call the Carolinas wasn't a coastline or a mountain range, and it wasn't even part of North America as we know it. It was just pieces of continental crust tucked inside a huge landmass, connected to areas that would one day become Africa and South America.

For hundreds of millions of years, this area was pretty quiet. But continents never stay still for long.

Rodinia Breaks Apart: The First Ocean (~750–550 Ma)

About 750 million years ago, Rodinia started to come apart. As the crust stretched and cracked, magma pushed its way up, and basalt spread all over the place. This activity led to the creation of a new ocean—the Iapetus Ocean, which people often call the "proto-Atlantic" (Hatcher, 2010).

This early rifting caused:

Volcanic rocks that eventually turned into greenstones

Thick layers of sediment buried deep in the Piedmont

The first outlines of what would become an eastern continental edge

By around 550 million years ago, the Carolinas weren't stuck in the middle of a supercontinent anymore; they were hanging out along the edge of a growing ocean basin.

Oceans Don’t Last Forever: Subduction and Volcanic Arcs (~550–450 Ma)

When the Iapetus Ocean started forming, parts of its ocean floor began sliding under other sections. This process, called subduction, created volcanic island arcs—kind of like the chains of volcanoes you see in Japan or the Aleutians today.

A bunch of these volcanic arcs showed up off the coast of what's now North America.

Over millions of years, these arcs drifted toward the continent and eventually collided with it, sticking to the edge of North America. This process, known as accretion, is how a lot of the Carolinas became part of the continent.

This all led to the first big mountain-building event in the Appalachians: the Taconic Orogeny, which happened around 470–440 million years ago. You can still find rocks from that time, like schists, gneisses, and volcanic leftovers, scattered around the Carolina Piedmont (Hibbard et al., 2002).

The Carolinas were starting to take shape, but the real action was still on the horizon.

4. More Collisions, Bigger Mountains: The Acadian Orogeny (~420–360 Ma)

The Taconic collision was only the warm-up. Not long after, new island arcs began drifting in from the east, setting the stage for the Acadian Orogeny. Though this event reached its full intensity farther north—in what is now New England—its effects ran deep into the southern Appalachians. The Piedmont felt that pressure: rocks were pushed to higher grades of metamorphism, the crust thickened, and entire belts of older formations were bent, folded, and sliced by major fault systems. Enormous river networks carried freshly eroded debris westward, spreading the fingerprints of this mountain-building episode far beyond the collision zone.

By this time, the Carolinas had become part of a sprawling, hybridized continental margin stitched together from volcanic arcs, wandering microcontinents, and repeated pulses of granite rising from below. The crust was bigger, hotter, and more complicated than ever. And still, the biggest collision was yet to come.

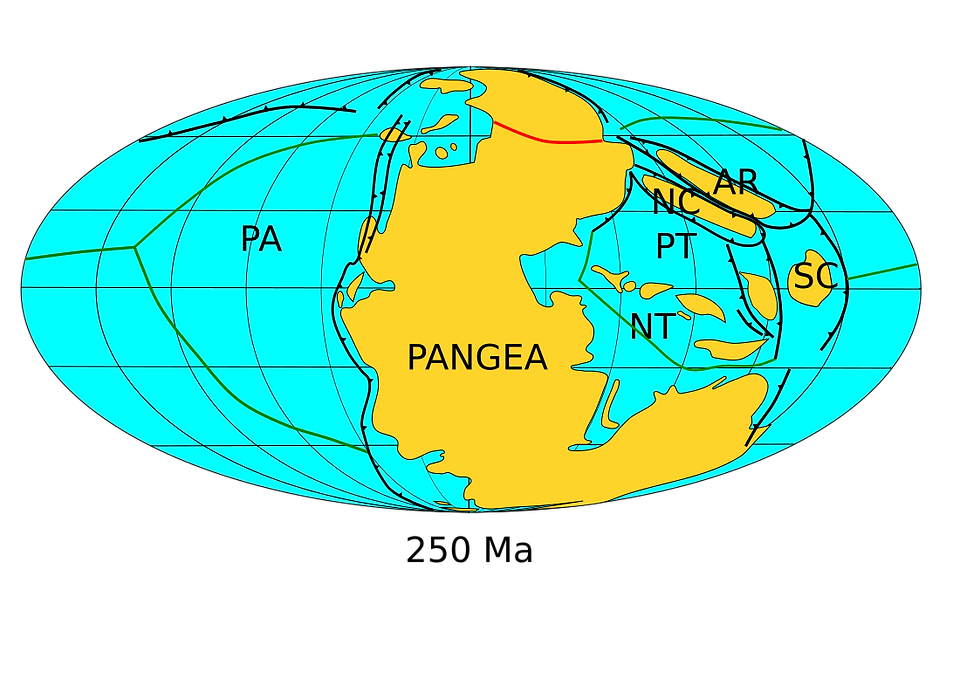

The Collision That Changed Everything: The Alleghanian Orogeny (~320–260 Ma)

Around 320 million years ago, the final drifting remnant of the ancient supercontinent Gondwana—carrying what is now Africa—closed in on North America. When the two continents finally collided, the impact was nothing short of catastrophic. This event, the Alleghanian Orogeny, completed the assembly of Pangea and built the highest phase of the Appalachian Mountains (Hatcher, 2010). Picture the Himalaya. Now picture them even larger. That is what rose across the Carolinas.

The collision shattered and reworked the crust at every scale. Deep shear zones cut through the interior, enormous thrust faults shoved entire plates of rock westward like a stack of warped pancakes, and broad swaths of older volcanic arcs were cooked and compressed into schists and gneisses. Magma surged upward during the crush of the continents, freezing into huge granite bodies that now anchor much of the region’s geology. This was the moment when the Blue Ridge—the crystalline core of the ancient Appalachians—took shape, and the underlying framework of the Piedmont was strengthened and locked into place.

By the end of the Alleghanian Orogeny, the Carolinas were no longer a collage of drifting terranes. They were fully welded to North America, part of a single, massive continental interior at the heart of Pangea.

Pangea Doesn’t Stick Around: A New Split, A New Ocean (~230–150 Ma)

Pangea held together for only about 70 to 80 million years before the seams began to pull apart. Around 230 million years ago, the region that would become the East Coast started to stretch and thin. That slow, persistent rifting eventually tore North America away from Africa and Europe. As the crust pulled apart, long, narrow rift valleys formed—Triassic basins like the Deep River and Dan River systems in North Carolina (Schlische, 2003). At the same time, enormous volumes of lava surged to the surface during one of the largest volcanic events in Earth’s history, the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province (CAMP).

As rifting continued and the continental blocks drifted away from each other, seawater finally flooded the widening gap. This was the birth of the Atlantic Ocean. Once the tearing stopped and the new ocean basin stabilized, the East Coast shifted into what geologists call a passive margin. No more mountain building—just the slow, patient work of erosion, subsidence, and sediment accumulating along the edge of a quiet continental shelf.

Erosion Takes Over: Sculpting the Carolinas (150 Ma–Present)

Once the Atlantic Ocean opened and the great age of rifting settled down, the Carolinas entered a long stretch of relative tectonic quiet. For the last 150 million years, the landscape has been shaped not by collisions or volcanoes, but by weathering, erosion, and the slow accumulation of sediment. Rock broke down grain by grain under the influence of water, chemistry, temperature, and time. Rivers transported that sediment toward the coast. Layer by layer, the Coastal Plain grew outward as sand, silt, and clay built up across a slowly sinking continental margin.

Out of this patient process emerged the three major regions we know today.

The Blue Ridge: Ancient Roots of a Lost Mountain Chain

The Blue Ridge is the stripped-down core of the old Appalachians—the deeply exhumed heart of a mountain range that once rivaled the Himalaya. The rocks here are tough: gneiss, schist, quartzite, all of them forged under intense heat and pressure and once buried miles beneath a colossal chain. Because those rocks resist erosion, they form steep slopes, fast rivers, and rugged peaks. Some of the oldest exposed rocks east of the Mississippi stand here, not because they have always been at the surface, but because hundreds of millions of years of erosion have finally peeled the crust down to its ancient foundation.

The Piedmont: The Quiet Heart of the Carolinas

Stretching from Greenville and Charlotte to Columbia and Raleigh, the Piedmont is a broad expanse of rolling uplands built on metamorphic and igneous rock—remnants of long-vanished volcanic arcs and microcontinents welded onto North America during the Paleozoic. Warm, humid climates over tens of millions of years rotted those rocks into the thick red clays the region is known for. Beneath the soil lie deep layers of saprolite, old river terraces, and a web of branching drainage systems. The Piedmont is, in a sense, the recycled interior of the Appalachians: what remains after the once-mighty mountains were reduced and rearranged into gentler hills.

The Coastal Plain: The Youngest Landscape

East of the Fall Line—from Fayetteville to Florence to Charleston—the geology shifts dramatically. Here, the land sits on layers of sand, mud, and marine sediments, many packed with fossils, that accumulated as sea levels rose and fell. Old shorelines appear as marine terraces stepping inland. River deltas and dune fields record shifting winds and currents. Offshore, the sediment pile grows ever thicker. Compared to the ancient backbone of the Appalachians, the Coastal Plain is geologically young—mostly younger than 100 million years—and still changing.

Climate Swings and the Ice Ages (~2.6 Ma–Present)

Although continental ice sheets never reached the Carolinas, the Ice Ages reshaped the region in subtler ways. During glacial peaks, cooler climates spread pine and spruce forests across the Piedmont, sea levels dropped more than 400 feet, and rivers cut deeper valleys as the continental shelf emerged into the air. With less vegetation to hold soil in place, erosion intensified. When the climate warmed, the opposite happened: sea levels rose, barrier islands migrated inland, marsh systems expanded, and the Coastal Plain thickened with new deposits. The coastline we see today is the product of that long back-and-forth between ice and interglacial warmth.

Modern Geological Processes: Slow but Persistent

Even now, the Carolinas are not static. The crust beneath the mountains continues to rebound as erosion removes weight—slowly lifting the Blue Ridge region like a cork rising in water. Rivers such as the Broad, Catawba, Yadkin, and Saluda keep carving channels and transporting sediment across the Piedmont. Meanwhile, the Coastal Plain is still subsiding under the cumulative weight of its own deposits. Old faults—some dating back to the Paleozoic and Mesozoic—occasionally adjust, producing the low-level seismicity that reminds us the crust is never truly still. The 1886 Charleston earthquake was simply the most dramatic example in recorded history.

Geology never stops. It only changes tempo.

Why the Carolinas Look the Way They Do

Taken together, the modern landscape reflects five deep-time truths. Mountain building created the Appalachians through a series of powerful collisions. Rifting tore the continent apart—twice—opening first the Iapetus Ocean and later the Atlantic. The Piedmont is a mosaic of volcanic arcs and microcontinents welded onto the continent. The Coastal Plain is a young veneer of sediments laid down by rivers and shifting seas. And above all, erosion has been the dominant force for more than 150 million years, slowly wearing the ancient mountains down to the bones we see today. The present terrain is not permanent—it’s just a moment in a much longer story.

Conclusion: A Landscape Made of Deep Time

Understanding the geology of the Carolinas isn’t just an academic exercise; it is a way of seeing the land more clearly. You begin to recognize why rivers follow the paths they do, why the Piedmont is clothed in red clay, why the mountains are soft ridges instead of jagged peaks, and why the coastline feels so fragile and always on the move. The Carolinas were shaped by collisions, rifting, volcanism, erosion, and an immense sweep of time. Every hill, terrace, and plain is a remnant of something that was once taller, hotter, deeper, or stranger.

The ground beneath your feet isn’t just scenery.

It’s the fossilized memory of worlds long gone.

References (APA 7th Edition)

Hatcher, R. D. (2010). The Appalachian orogen: A brief summary. In R. Tollo et al. (Eds.), From Rodinia to Pangea: The Lithotectonic Record of the Appalachian Region (pp. 1–19). Geological Society of America.

Hibbard, J. P., van Staal, C. R., & Rankin, D. W. (2002). Comparative analysis of the geological evolution of the northern and southern Appalachian orogens: A record of accretion and continental collision. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 114(5), 593–614.

Schlische, R. W. (2003). Progress in understanding the structural geology, basin evolution, and tectonic history of the eastern North American rift system. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 115(3), 1–20.

Tollo, R. P., Bartholomew, M. J., Hibbard, J. P., & Karabinos, P. (Eds.). (2010). From Rodinia to Pangea: The Lithotectonic Record of the Appalachian Region. Geological Society of America.

U.S. Geological Survey. (2023). Geologic Provinces of the United States: Appalachians, Piedmont, Coastal Plain. https://www.usgs.gov

Comments